Fifty years ago, my life changed forever. And that’s a hard thing to say about the year where you turn seven, but it’s undeniably true because that was the year when I discovered baseball.

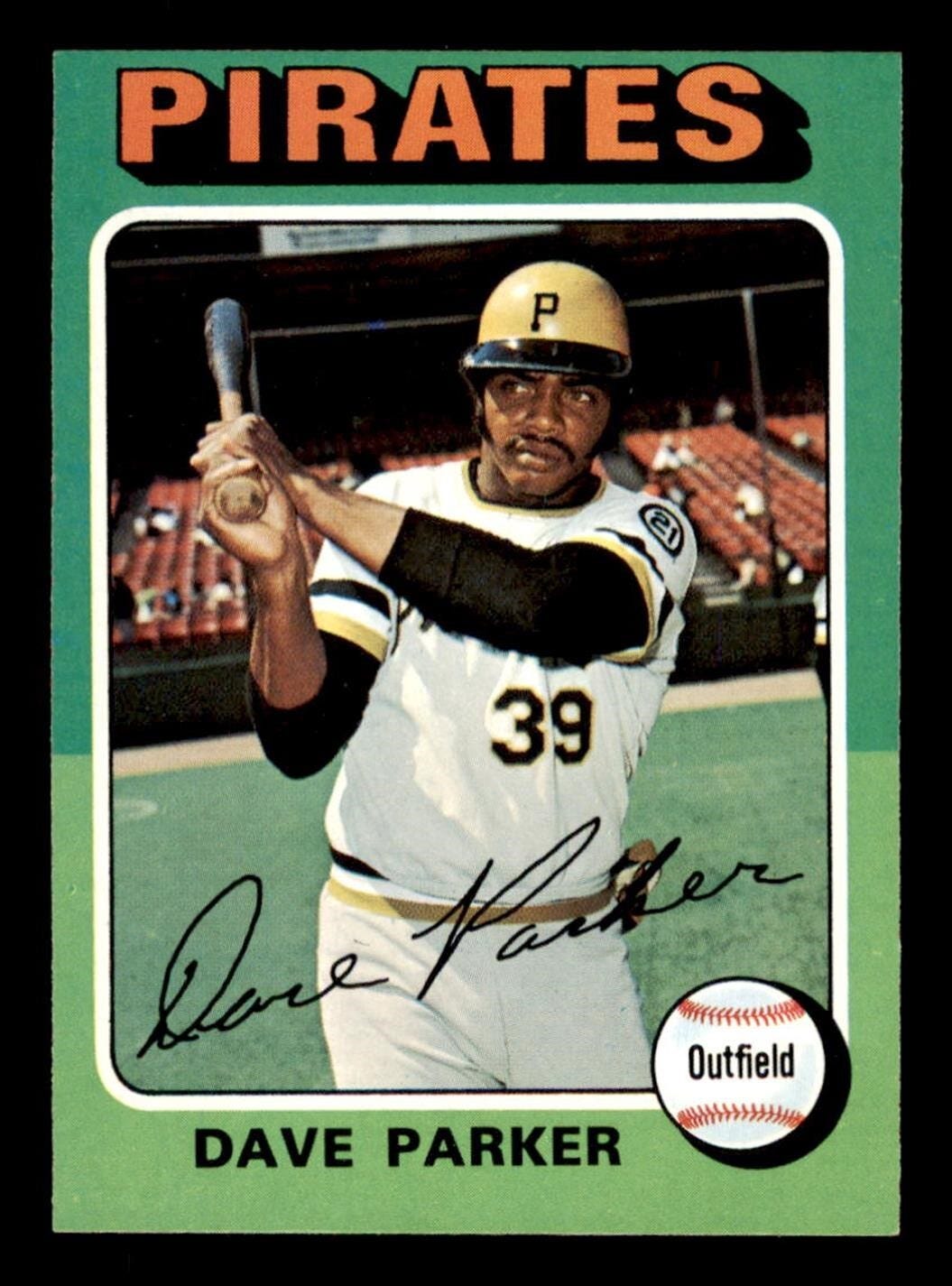

Baseball cards, similar to the ones shown above, were the game’s first delivery system. I found that for just a few pennies, I could acquire a number of colorful little carboard representations of ballplayers. And these cards were nothing if not colorful, in a way that baseball cards never would be again. There was yellow on green and blue on orange and even purple on pink, and each had the team name splashed across the top in another color, just to make it look even more technicolor. And why not some green on green, and some orange to top it all off? The 70s really were a wild time.

The two players shown here—each with a sort of bemused look on his face—were doubtlessly holding a pose for a photographer, the way almost every card from the Topps company looked that year. They had used some action shots from previous years in the decade, but they seemed pretty awkward at times, so there was a large amount of posing, generally during Spring Training season, seen in the cards from that season. Not that a young kid with limited experience with the game cared very much about that, though. These were ballplayers, doing ballplayer things, and that was good enough.

Since both players were still in the early years of their playing careers, each of the stops on their paths to the major leagues were listed on the back of their cards. I couldn’t care less about where either player had played, or what their stats were at any given place. One of the two players had played in a place called Coos Bay, which might as well have been located on Pluto for all I knew. But there it was anyway, just in case I was interested.

More established players in the majors had enough career stats that they didn’t need their minor league exploits to be recounted on their playing cards. And if these guys were lucky (and one of them eventually would be), they would one day reach that point, too. But there was space that had to be filled, and if it meant that a .228-hitting season at Waterbury would need shared with the youth of America, then so be it.

When the stats by themselves weren’t enough, that’s where the verbiage would come into play. Both were given just three lines of text, although four could have probably fit comfortably into the space as well. Topps padded both the top and bottom margins, and dared somebody to take notice. One of the players was described as having “good power combined with outstanding speed and a strong arm.” Not such a bad turn of phrase there, when three of the five “tools” that a star player should have are all mentioned at once.

The other player was noted by the Topps company for having both the speed and youth that his club was looking for. But then hyperbole seemed to get out ahead of them a little bit when they declared that the player “has super-star potential.” For a young kid in the mid-1970s, that word conjured up images of a televised competition where athletes would perform feats of strength and agility for all the world to see. You didn’t use the word “super-star” lightly in those days, but someone at the Topps company either didn’t know that or didn’t seem to shy away from it.

Fifty years later, each of these men tragically passed away. One of them was even set to be inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame later this year, after a long playing career that included batting titles, All-Star team appearances, and World Series championships. Clearly, he was the one that Topps had heralded as having “super-star potential” five decades ago, because he went on to actually do superstar things. That makes sense, right?

Well, not so much. The back of Dave Parker’s baseball card from 1975 was right about his power, and certainly about his arm, but they didn’t apply the word “super-star” to him. They did, however, apply this term to young Vic Harris on the back of his 1975 card. The truth is that Harris’ best year in the majors, when he played 155 games with the Texas Rangers in 1973, was already behind him by the time this card appeared. When the 1975 season ended he was traded to the St. Louis Cardinals, and after the 1976 season he was traded to the San Francisco Giants, where he spent two years in a backup role. He then had three pretty good seasons playing in Japan, and returned for one season at Triple-A before leaving baseball at age 34.

Vic Harris’ major league output totaled 13 homers and 121 RBI across eight different seasons. By way of contrast, in the year after Vic Harris left the game, Dave Parker hit 34 homers and drove in 125 runs in one season. Granted, it was also the year that he tarnished his reputation by testifying against a cocaine dealer after the season was over. Vic Harris never had to go through any of that in his career, at least. But if Topps was going to label one young ballplayer as being a potential “super-star,” they surely picked the wrong one.

That’s all for now. Until next time…..

I was a Mets fan growing up. But in the ‘70s I somehow kept an eye on the Pirates who were fun to watch!