I’ve said repeatedly that baseball meant more to me in the 1970s than at any other point in time. But I should hasten to add that baseball continued to have significant meaning to me in the years after that, as well. And the passing of Fernando Valenzuela yesterday, on the eve of a World Series matchup of his Dodgers franchise against the New York Yankees, reminds me of how strong those ties have remained in my memory.

The number 34 will be worn by all Dodger players in the upcoming Series, and that’s a fitting tribute. I remember well when Junior Gilliam, who had been a player and a coach with the Dodger organization, passed away just before the 1978 World Series, and the team retired his number 19 and all the players wore a patch with that number on it during the Series. In fact, Fernando’s number 34 is now retired across the Mexican League, similar to the league-wide retirement of Jackie Robinson’s number 42 in MLB. It’s a mark of highest respect to say that no other player—on any team—will ever wear one player’s number again. And Fernando is certainly worthy of such an honor.

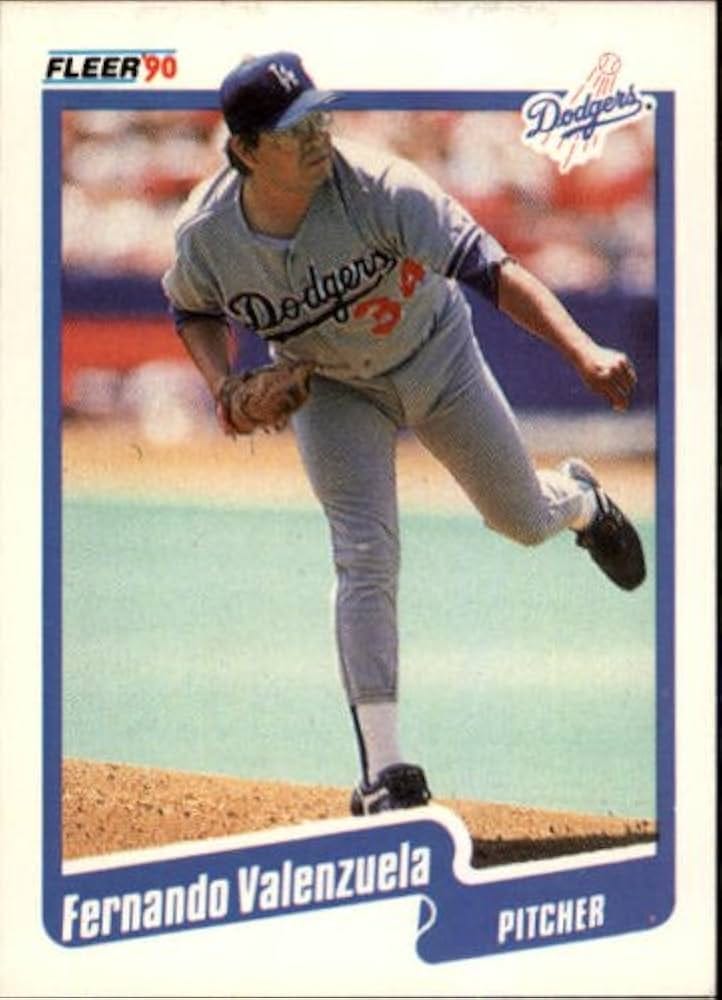

The card above, dated in 1990, marks the final year that Fernando pitched with the Dodgers. If life were a movie, he would have ended his playing career with the franchise where he burst onto the scene with an unspeakable intensity back in 1981. Fernandomania was the story of the year in baseball, at least until the players’ strike shut down the season in early June.

The loss of two months’ worth of games was significant, but it all ended up well enough for Fernando (who won the National League’s Rookie of the Year and Cy Young Awards) and the Dodgers (who captured their fifth World Series title). He remained with the Dodgers through the end of the decade, but was left off the post-season roster after a sub-par season in 1988, when the Dodgers won their most recent championship.

Fernando pitched his first and only career no-hitter with the Dodgers in 1990, the year this card was issued, but the following year he was cut by the team in spring training, and his post-Dodgers playing career included stops in several places, including the Mexican League, before reaching its final conclusion with St. Louis in 1997.

Fernando has already beaten the Yankees once—by pitching a complete game against them in the 1981 Series—so who’s to say that he can’t help the Dodgers out again, from wherever his new environs might be?

Here’s to an exciting finish over the next seven games (and hopefully not any less than that).

I didn't know about the Jerry Reuss story until just recently, but it seems like the opening lines of Eminem's "Lose Yourself" brought to life: "If you had one chance, one opportunity, would you capture it, or just let it all slip?" Fernando captured it, for certain. Thanks for sharing your memories of him and what it all meant. It was something that doesn't come around very often.

Not many players can claim they were the zeitgeist for their ethnic and national origins. The Dodgers then did not include Mexican culture or even nod toward the Latinos that made up so much of the city.

It would be a great story if El Toro changed how the owners saw the Dodgers. The closest we got was Vin Scully and his description machine of Fernando/Fernando mania. Vin has passed, so let us forgive him for the embarrassing sombrero references. But the front office and ownership had to start somewhere.

No, the Dodgers were to stumble out of the O’Malley years, into the shitshow that was Fox, and then McCourt. Now, McCourt was not a disaster for the rebuild the Dodgers needed. The McCourts were a disaster in every other way.

The new Guggenheim leadership has made changes. The many Latin nationalities are now a big part of how we see the Dodgers and how the team sees itself. What should have been evident in 1981 took a few more decades to become real.

I was in attendance at the Fernando Tribute last year. Edward James Olmos carried the flag for those who will not forget what it was like between the team and the enormous Mexican population here before Fernando. Politicians embraced 34, and for the most part, it sounded like they meant it. Remembering Fernando Mania brings the youth out in all of us who were baseball conscious in 1981.

Two quick thoughts. First, Mark the Bird Fidritch may have been as big a story as Fernando, but he came and went without changing much. We are still benefiting from what Fernando unleashed.

Second, my grandmother took my sister and brother to opening day in 1981, expecting to see Jerry Reuse on the mound. Instead, they were present at the creation of modern baseball culture.